Hello and welcome to Technocracy. I am Heena Goswami, editorial consultant with IGPP - Institute for Governance, Policies and Politics, New Delhi.

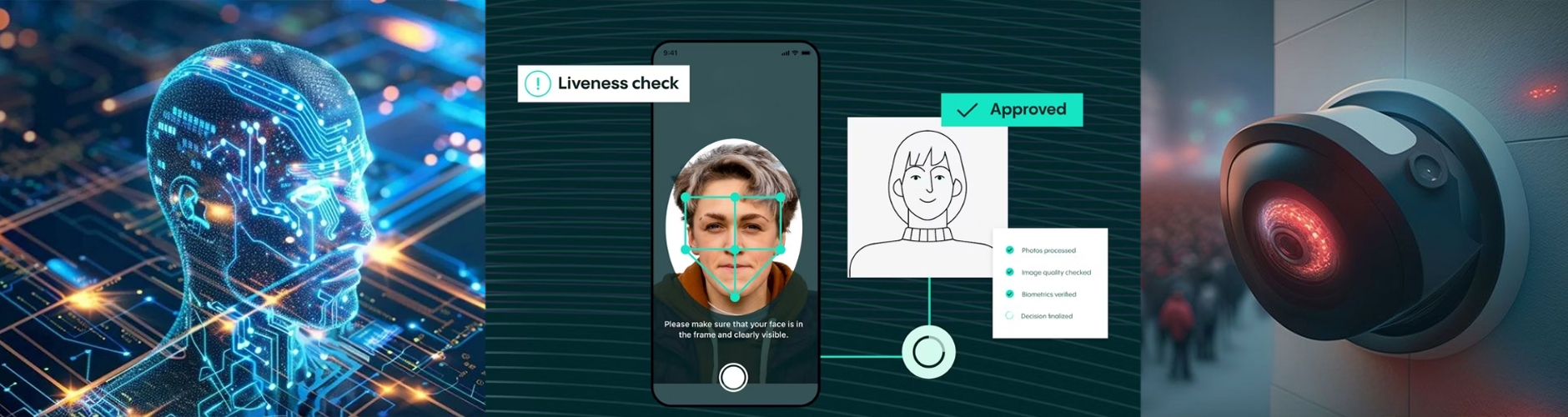

The way AI has come to be integrated into our lives, sometimes we aren’t even aware that the technology we are using is AI and that is something that has the technology also has in common with surveillance. Whether it’s the traffic monitoring camera that takes a picture of you or the CCTV at your office’s gate, we aren’t even aware that we are constantly under watch. Increased crime rate, unsafe neighborhoods, fears of harassment may make us clamor for even increased watch through deployment of facial recognition techniques, CCTVs, biometric checks. Its also not just the matter of state surveillance but the applications that we use on our phone, social media platforms that have our location all the time, know about our health better than our doctors and can tell our friends and families apart.

The relationship between AI and surveillance is deeply intertwined. It is, through this data, derived from us through our applications or from what is available publicly about us that artificial intelligence technologies are improved and then further deployed to keep an even keener watch on us and understand us better. The big data that is used to train artificial intelligence system include almost everything individuals do– searching online; sharing and transmitting day to day information with government, companies and social media; even just walking around with a smartphone creates vast amounts of information about individuals.

But, what is the downside, you may ask. Privacy. Take for example, the use of CCTVs, using CCTV cameras in public places is quite common these days and most people don’t see it as a big problem. But when these cameras are used together with facial recognition software, they can become a powerful system that watches people too closely and can affect their privacy. A recent UN report has warned that people’s right to privacy is coming under ever greater pressure from the use of modern networked digital technologies whose features make them formidable tools for surveillance, control and oppression.

The way we understand things like giving permission, being informed, and having control over our personal information is being challenged like never before because of AI. And most of the talk about privacy and AI does not think enough about the gap in power between big companies or government that collect our data, and the normal people who give that data. The opaqueness and in explainability of AI applications and algorithms also make is difficult to determine what data was used for what purpose and how it led to a certain result, making it difficult to fix accountability.

What is also scary is that AI can find patterns that humans can’t see, learn from data, and guess things about people or groups. This means AI can create new information that is hard to find or was not clearly given by the person. For example, an AI used in hiring might guess someone’s political views from other simple details they gave and use that guess while deciding whether to hire them or not.

And what if, the government also has access to the data produced by your applications. This is exactly what has made the recently introduced Income Tax Bill 2025 controversial as its provisions grant tax officials access to citizens' digital and financial spaces. The bill has been criticized for allowing tax authorities to access emails, social media accounts, bank details, and trading transactions without a warrant or prior notice, solely based on suspicion. Such laws that allow governments to access our chats, photos, spending habits, will have a negative impact on our fundamental rights. In 2018, the Home Ministry even allowed ten central agencies to watch, check, and read any data from any computer, for the purpose of “national security”.

So, how do we ensure that our data, whether collected by applications on our phone or by government agencies is not used for surveillance purposes. For starters, rules like data minimization and purpose limitation can be made which say companies should only collect the data they need for a specific reason and such rules do exist. According to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), no company or organisation should keep a person’s personal data for longer than needed. The data should be kept only as long as it is required for the purpose it was collected. However, no such law exists in India at the moment as the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act), while passed by Parliament, its specific rules and regulations, are yet to be officially notified.

The right to privacy is protected as an inherent part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution. And whether from the government or from applications in our phone, we do need privacy.

AI can bring big benefits to healthcare, law courts, and government services. But like many other technologies, AI also creates social, technical, and legal problems, especially in how we understand and protect people’s privacy and personal information.The benefits of AI should not make us compromise with our right to privacy and the choice shouldn’t be between technology and privacy but rather technology should be designed and deployed in a manner that guarantees our privacy, as envisioned by our Constitution.

To further understand the inter-relationship between digital technologies and surveillance, today we are joined by Mr. Jay Stanley. Mr. Stanley is senior policy analyst with theAmerican Civil Liberties Union Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, where he researches, writes and speaks about technology-related privacy and civil liberties issues and their future. He is the editor of the ACLU's Free Future blog and has authored and co-authored a variety of influential ACLU reports on privacy and technology topics.

So my first question to you is that in this day and age, where we have Google, Instagram, CCTV, biometrics everywhere—do we have any privacy at all? I mean, is the state watching over us all the time?

I would say that privacy is on life support, but it is not dead. We have lost far more privacy than we should have lost. We are monitored in ways that would be unimaginable in, say, the 1970s. If you had told Americans in the 1970s that there would be entities that were tracking our locations everywhere we go using a tracker that we keep in our pockets, they would say, "Oh, I guess, you know, we're living in a totalitarian state. Maybe the Soviets have taken over the world." But here we are.

And internet tracking companies like data brokers are gathering lots of information about us, and surveillance technologies such as cameras, license plate readers are increasingly growing. In some cases, they're in early stages, but we can expect that they will spread everywhere around the world if policymakers and the public don't put a stop to it.

So our privacy is in bad shape. At the same time, it's a little too glib to say, "Oh, you know, we've lost all our privacy already, so just throw up your hands and stop fighting," because we still do have a lot of privacy. And where it's lost, people still get mad. You know, most of your conversations are not recorded. They might be recorded if you're having them on social media, and who you call and when may be recorded by the telephone carriers. But at least in the United States, they still can't listen to the content of your calls without a warrant.

I should say that my organization is very US-centric, so my perspective comes from the American experience, and I can share that with you. But I think that a lot of things that happen in the United States will probably spread around the world where they haven't already.

Most of the time, we are not monitored. We do have a lot of space to have conversations. We are not living in China. We are not living in the Soviet Union. And so you have to be careful while bemoaning the privacy that we have lost—not throwing up your hands and just saying the war is over, we have lost—but to recognize that we still have privacy in a lot of ways that people would be very angry if they lost.

One argument that is given to us, for example, with the deployment of CCTV cameras or facial recognition techniques or biometric checks, is to ensure that crimes don't increase or that people are safe. But that never really happens. I mean, crime rates keep increasing all the time. We have more cases of harassment. I mean, the harassment, the crime rates — they don't come down, they just go up. So then, how essential, how logical is this argument, and how sensible is this tradeoff between surveillance and safety?

Yeah, well, I think that, you know, a lot of these technologies increase the power of government agencies and, in some cases, companies. And they like having their power increased. The reason that they can get their power increased is by scaring people and saying, "You need this." And they point to particular stories, and they say this technology will save the day. Maybe they point to particular examples where the technology does help them.

But you can't just accept a technology because a government agency points to one success story. The question is: is it really that successful? How frequently do those successes happen? How important are they? Are you stopping jaywalkers? Are you stopping significant crimes?

And what are the side effects of the technology? What are the side effects for our freedom? How many innocent people are caught up, in addition to the actual bad people that you catch? You have to ask all these questions.

In many cases, these technologies cost a lot of money. There's a lot of money that changes hands. Contractors are happy; they're pushing them on the government agencies. Sometimes, the government agencies want them. And yet, we're trading away privacy for not very much safety — if at all. And it's a bad deal.

So, you have to ask sharp questions, like a suspicious buyer, before you allow your government agencies to have more power that comes from technology. These new technologies are granting new powers to government that government has never had before in all of human history. They are brand new. We don't really know how they're going to work out in many cases, because we don't know what the side effects will be on our feelings of freedom — on having chilling effects, making us feel like we can't express ourselves because we're being watched.

So, we have a long history of all kinds of technologies in the United States being pushed by government agencies. First of all, they try and push fear at you and make you more and more afraid. And then, second of all, they claim that these technologies will fix them — when it doesn't really.

And then they put the wrong people in jail for the wrong crimes, and crime rates never go down. My next question is rather naive and simplistic, and somewhat obvious, but what possible fallouts do you see with such increased surveillance all over the world? I mean, all over the world we have CCTV cameras in public places—at airports, bus stops, schools, offices, buildings. We have facial recognition techniques at religious places in India. So what possible fallouts do you see with such increased surveillance?

Well, I think that at the top level, it increases the power of authorities—of government officials, sometimes corporate entities, companies—over individuals. It shifts power from and freedom from individuals to these large institutions. If a camera's recording everything you do, that's not empowering you; it is empowering somebody else. And the same goes with other surveillance technologies besides cameras—data collection and so forth: where you're shopping, what you're buying, your finances, your medical life, your communications, your travel. None of that is being collected to empower you. Maybe in certain cases, in narrow cases, it could be helpful to you to have data collected, but in those cases, it should be your choice. It should be under your control, and you should be able to delete it if you want. But mostly, none of that is true.

So that's one issue. Another issue is that it can lead to abuses. It can lead to individual people in government or companies using this technology against people in abusive ways. They might be going after you because they don't like your political views. They might be going after you because you are dating his ex-wife. They might be going after you for a variety of abusive reasons.

We've seen bribery cases where a police officer scanned all the license plates in a gay bar in Washington, DC, and then used police databases to find out who was married to a woman, and then tried to bribe them.

And so, from sort of authoritarian abuse to smaller-scale abuse, it also just creates chilling effects. It makes people not feel free when they are under the eye of all this data collection. It makes them realize that they're being watched. It makes them monitor themselves. Sociologists call it the third eye. You might be thinking about yourself, but you're also wondering how you appear to those who are watching you. And that makes you not feel free. It makes you perhaps afraid to be unusual or to stand out, to be an anomaly—in the terminology of AI. And that stifles freedom. It stifles new social movements. It stifles social progress and social change. It enhances conformity.

Sociologists have shown that people need an eye from the refuge of their community. They need space where they are not under the eye of their community or of the authorities to be healthy. Constantly being watched, psychologists have shown in many, many studies, creates a sensation of stress and tension. And it's not how free people should have to live.

We often hear, at least in India, that you know, I have nothing to hide, I don't have any adverse political opinion, or I'm not doing anything criminal, so why should I fear the state having constant eyes on me? Or why should I fear the CCTV cameras in my neighborhood, or you know, at places where they shouldn't be? Is that something that you also come across, and how do you respond to that?

Yeah, I think we in the privacy community hear that all the time. I'm not doing anything wrong, so I don't have anything to hide. Why should I care? And there's a number of answers to that. Number one, some people—you might not have anything to hide, but some people do have something to hide, and it's not something that the government should have the power to reveal. People hide a lot of things even from their closest friends and family—the things about their sexuality, their health, that they're pregnant, that they're in love with somebody else. You know, maybe your private life is very simple, but there are others whose isn't, and you should want to live in a world where those people don't have to have their private life turned inside out. There's a reason we call it a private life.

Number two, you might not have anything to hide, but the government might think you do. The government makes errors, and if we allow the government to watch everybody just in case we might be involved in wrongdoing, mistakes will be made. There are always false positives and false negative rates with any technology.

And number three, are you sure you have nothing to hide? There's a lot of laws on the books, a lot of very complicated laws on the books, and police and prosecutors have a lot of discretion with which to interpret those laws. So maybe they make a mistake and they go after you, and then they realize they made a mistake. But meanwhile, because they have so much data about you, they found that you are— you know, in the United States, there are obscure laws against owning leather from endangered species from Latin America. Maybe your wallet is made out of that, or who knows. But they can find something often on somebody even if they are a pretty normal person, because the laws are so complex.

And then also, everybody hides a lot of things even though they're not wrong. People don't want to be seen naked in public. People don't want anybody listening when you sing in the shower. It doesn't mean there's anything wrong with singing in the shower, but maybe you don't want somebody looking over every piece of food that you've bought in the last year. There's nothing wrong with buying food. Maybe there's nothing unusual about your patterns, but it's just intrusive—just like somebody listening to you sing in the shower. Why does somebody need to see all the food you've bought in the last year?

You might not care about hiding things, but you might be discriminated against anyway. Maybe you don't care about somebody looking at all your food and looking at all your finances and stuff, but companies may use that data against you by making bad decisions or not making good offers for you.

And then finally, privacy is about broader values than just hiding things. As I was saying, it's about the importance of having a refuge from the eye of the community and space to explore yourself, to expand your identity, and explore different identities and the like without having to worry about being monitored every second.

One feature of how the technology has come to be integrated into our lives is that we're not just scared of the surveillance by the state, but now we're also scared of big tech companies that are watching us all the time. And they—I mean, they must know more about us than sometimes what we know, like what to buy or, you know, what exactly are we looking for. Like, sometimes you'll go to YouTube and find the exact song that you were thinking of but you could not just—Google. Is that somewhat more worrisome than the state surveillance itself? Or, I mean, how do you—what do you think about-

I don't know about ranking it, but it's very worrisome. Google cannot put you in jail, which the government can do. On the other hand, at least in the United States, I mean, most of your—most of our interactions are not with the government but are with companies, and they have a much richer amount of data about us than even the government probably does. And that data is more granular; it's more in the nitty-gritty of your daily life. And so in that sense, it's a huge threat.

On the other hand, there's often a very blurry line between government collection of data and private company collection of data because the government can often access the data that a private company gains. In the United States, the authorities have plentiful legal authorities to subpoena the information, to issue legal demands for the information, and if all else fails, the government sometimes just buys the information about people.

And so, in the United States, we have a Privacy Act which bars the government from keeping dossiers and files about people if they're not involved in the criminal justice system or the like. But meanwhile, we have these big, giant billion-dollar companies that are basically doing what the Stasi in East Germany did and maintaining files on everybody—every piece of data they can get their hands on about us—they put into a file, and they sell it for commercial purposes. And then government agencies go around the Privacy Act by buying those dossiers, even though they're not allowed to maintain them themselves.

So that's a huge problem. And there's been proposals in the U.S. to fix that by banning the government from doing that, but they haven't passed Congress yet. But I don't think you need to rank which is a bigger threat. I mean, we need to work to restore our privacy on all fronts. And, you know, our privacy is in a really bad shape right now.

But in some ways, I am optimistic for the future. I think that, you know, the arc of history is long, but it bends towards privacy. I think these technologies are happening so fast, and these new practices are happening so fast, that the companies and government agencies just engage in a land grab, and they start collecting data on us and spying on us. And it takes people a long time to realize that it's happening, to get angry about it, and to push back. But in history, we have seen that, over time, things tend to revert to privacy because people demand it, and they don't like not having it.

And so there's a gravitational pull back towards increased privacy. For example, in the United States, when they first started running the telegrams in—I don't know, what was it, the 1860s or the like—the telegram companies were reading everybody's telegrams, and they were making trades on Wall Street based on inside information. And it took like 40 years, but eventually Congress passed privacy protections.

We saw that a lot of the monarchs of Europe were reading everybody's mail—which, in the late Middle Ages or the Renaissance era, was mostly nobles—but they were reading all their mail, and eventually, over a couple hundred years, everybody pushed back and all—basically all of them—stopped doing it. Until the 20th century, at least, with the rise of the NSA and the like.

So yeah, I think you have to worry about both.

How do we draw the limits then, or like, what would be your recommendations that these are the guard rails that are vital to ensure that our privacy is protected and our liberty is not at stake in this age of AI from both the state and the big techs?

Yeah, I think there are some general principles, and then you need specific rules for certain technologies that are specific to those technologies. But in terms of general principles, there are these things called the fair information privacy practices, or FIPS, and they basically say that, you know, you need to have notice so you're aware of when data is collected about you, and you should have choice and control over when data is collected about you. Data that's collected for one purpose shouldn't be used for other purposes without your affirmative meaningful permission—not some sentence very deep and nine-point font in a click-through agreement, but meaningful choice. And that your data should be kept with good security and things like that.

And those are just what most people around the world recognize as sort of fundamental fairness. Don't watch me when I don't know you're watching me, where it's reasonable, like I should have choice here and control over my data and the like. You know, privacy is not about hiding your whole life from everybody. Some people are happy to chat about their sex lives online. Other people don't reveal anything about themselves and keep everything very close to their vest, and that's fine. The question is, do you have control over it, or is information about you ripped away by a potentially hostile party who does not have your interests at heart?

And then, I think you do need specific rules. You need rules for how, for example, with video cameras—how long is that data kept, who has access to it, who is it shared with, if anybody, what purpose is it used for? Can anybody in the security office just browse through it looking for pretty women or looking for random things? Or do they have to have a specific purpose for looking at it? And are there audits? Are there logs kept of how it's used, and are there audits—somebody looking at the logs to make sure that the data is not being used for abusive purposes or the like? And that should apply not just to video cameras but to a lot of other areas too where data is collected.

So, you know, we know what we need to do and what most people consider sort of fair practices that will protect people and make them feel like they're not being watched every day from the moment they leave their house till they get home at night and maybe in some ways inside their home with a lot of the technology—the internet of things, and cameras in the home, and so forth.

We know what we need to do, we just need to do it. And again, there's a lot of big issues in this world, and privacy is not the top for anybody most of the time. But sometimes there is a gravitational pull. People—polls show people really don't like, for example, internet monitoring and monitoring of what websites they're watching, but they feel like there's nothing they can do about it. But I think that discomfort that people feel over time will translate into reform.

Thank you so much for joining us today, and thank you for this very enlightening and insightful conversation. If you enjoyed watching this episode of Technocracy, please like, share, and subscribe to our channel for more AI-related conversation. You can also watch IGP Expert Talks AI special series.