Hello and welcome to the latest episode of Technocracy. I am Heena Goswami, Editorial Consultant with IGPP, Institute for Governance, Policies and Politics, New Delhi. In this episode, we take up a term that was always part of our political dictionary but has acquired due significance these days. And the term is "oligarchy."

It all started when a somewhat eccentric billionaire—a man-child genius—decided to donate to the now U.S. President’s election campaign. Now, the President of the U.S., Donald J. Trump, is not new to controversy, and his election even led many naysayers to argue that the doomsday is right around the corner. And such pessimistic opinion got further boosted by the outgoing President Joe Biden’s farewell address, which warned Americans that an oligarchy is taking shape in America, driven by a tech-industrial complex.

So, what is this tech oligarchy everyone is talking about? The term "oligarchy" was coined by Aristotle in 4th century BC and refers to a form of government where a small group of people—typically the very wealthy—hold most or all of the power, using it to make decisions that serve their own interest rather than those of the general public.

Now, it is no secret that political parties and policies they implement or advocate have for long favored very wealthy people, corporations, and business groups. A study by political scientists Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University, as far back as in 2014, concluded that the influence of ordinary citizens in political outcomes was at a non-significant, near-zero level—and America was not a democracy at all but a functional oligarchy.

There is an urgent need for timely action by the organizations working to prevent child sexual abuse material online. During the study, it was found that CyberTipline, a global cleaner of CSAM and mechanism in the platforms to remove CSAM, is slow and despite reports made, no action was taken for a month; this suggests a lack of enforcement.

So, how is it that the rich and wealthy individuals are able to influence a government elected through popular support? Firstly, the sheer amount of money spent on American elections and the large sums of money raised by super PACs indirectly influence the policy decisions of candidates once they are in office. But other than this quasi-legal monetary influence, there has always been a backdoor corporate influence on politics and politicians.

There's also logic to large corporations with lots of money at stake and governments looking for better investment in the nation and employment opportunities for its citizens to have somewhat amicable relations.

Even the fears of an oligarchy shaping up are not new to the U.S. During the Gilded Age, figures like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan built monopolies that shaped government policies and election outcomes in their favor. And as political power was concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy elites, economic inequality skyrocketed—something similar to what we are seeing today. However, this era of oligarchic dominance eventually led to progressive reforms like antitrust laws and labor protection aimed at breaking up monopolies and curbing the power of the ultra-rich.

So what is new about these fears? Wouldn't the new tech oligarchy eventually fade out? Political observers say that the outsized influence of the elite few, which work behind closed doors, is now being legitimized, made over, and built into power systems.

Musk is one of the 13 billionaires nominated by Trump for government posts, adding up to what has been known as now the wealthiest presidential administration in modern U.S. history. Days after the election, American news agencies reported that Musk was weighing in on key White House staffing decisions and had even joined Trump on a phone call with the Ukrainian president. Some fear he could even gain regulatory authority over federal agencies that oversee his companies like Tesla, SpaceX, and Starlink.

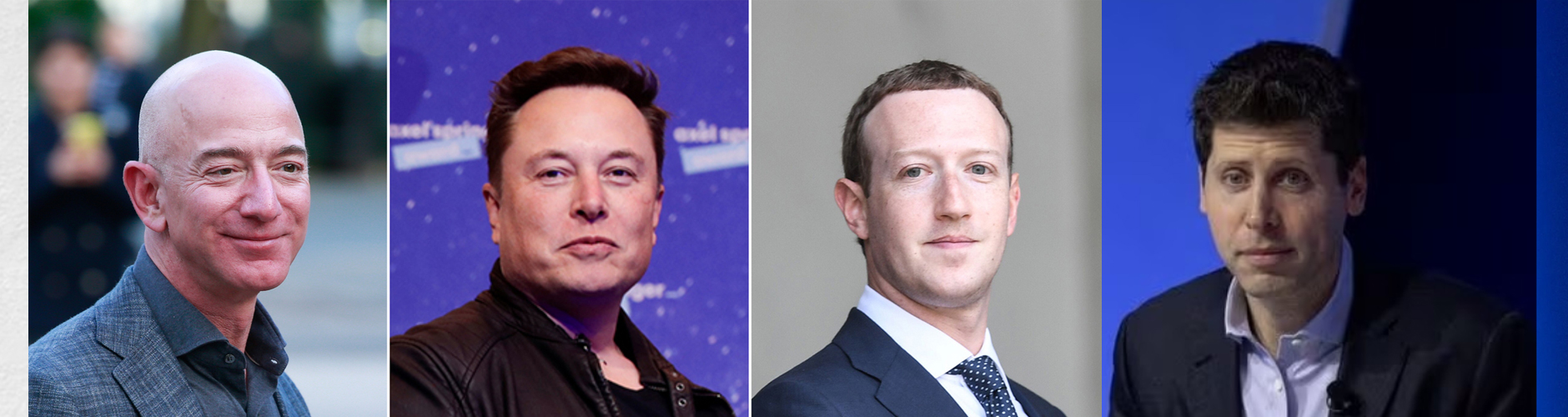

And Musk is not alone. Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Tim Cook, Sam Altman are all cozying up to Trump. They pledged million-dollar donations to Trump’s inaugural fund through their companies. And Zuckerberg even dismantled Meta’s DEI and fact-checking programs and relaxed its hate speech policies affecting Facebook and Instagram. And Bezos reportedly blocked The Washington Post, which he owns, from making a planned endorsement of Kamala Harris.

Many of these tech leaders tend to financially gain from Trump’s policies that favor the unrestricted growth of tech and unregulated artificial intelligence. Take for example Elon Musk, who has purchased an unelected, unprecedented leading position with President Trump’s administration by pouring millions of dollars into his election campaign. And the Trump administration in turn has fired top officials and career employees who were leading investigations, enforcement matters, or lawsuits pending against Mr. Musk’s companies.

Similarly, Zuckerberg’s gambit is that while his social media platforms will govern the way the government likes, the government will do things he’s demanding—such as dismantling the Consumer Finance Protection Board that was set up after 2008 to protect citizens from financial crimes—and force Canada, the UK, and the EU to drop any regulation of his companies.

Journalist Matt Hatfield argues that what is also frightening about these new-age oligarchs is that not only do they have vast financial resources for directly funding their pet causes, they can tilt the scales of their platforms to benefit beliefs they support and suppress speech they don’t. They have a power unprecedented in human history—platform-derived power—to directly surveil, promote, and suppress the conversation of millions of people simultaneously. It is no longer about resisting unwise or anti-innovation tech policy; it is about reordering how government works to serve their interest and function like their businesses, not as socially accountable institutions, he alleges.

So, are there any silver linings to these dark clouds? Are the worst fears of U.S. citizens about to come true? Or can the course be somewhat reversed?

To answer these questions, today we are joined by Professor Barbara A. Perry and Mr. Giorgio Castiglia. Barbara A. Perry is the Jay W. Newman Professor of Governance at the Miller Center, where she co-directs the Presidential Oral History Program. She has authored or edited about 17 books on presidents, first ladies, the Kennedy family, the Supreme Court, civil rights, and civil liberties. Mr. Giorgio Castiglia is an economic policy analyst for the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation's Schumpeter Project, where he focuses on the economics of antitrust and competition policy. His writing has appeared in Concurrences, RealClearMarkets, EconLog, Discourse Magazine, among other publications.

Now, Professor Perry and Mr. Giorgio, to begin with, both of you — I'm throwing the same question at both of you — that ever since the election of President Trump, we have been hearing these repeated charges that an oligarchy is shaping up in the U.S. How true is that? Is that real? Is the fear real? Is that the new reality of the U.S.? Professor Perry?

I would agree with that analysis — that the United States has moved, under the Trump administration, particularly this second term, but starting with the election itself — in that Elon Musk, the richest man in the world as people know, gave so many millions of dollars to the Trump campaign. I think it was $250 million to, in effect, buy the presidency — that is B-U-I, buy the presidency, purchase the presidency for Donald Trump.

And very much different from other times when there have been very rich and wealthy Americans involved in American politics and presidential politics, including wealthy Americans who've been elected president. So I don't want to indicate that it's totally unique, but it is unique in that this is the richest man in the world giving more money to one candidate than any other, and then creating a position for himself — and, I will put in inverted commas or quotes — a department, the so-called "Doge," the Department of Government Efficiency. So, in effect, is running a major part of the American government.

And if that's not the definition of oligarchy — and another word that was used in the era of robber barons in the United States in sort of the 1890s — that it's a plutocracy. It's where the business people, and a particularly kind of business people with certain interests and certain expertises in their own business areas of technocracy, as we say, or techno-people, are running the country.

Yes. So, in brief, I think the case for this is a bit overstated personally. I think in general this argument tends to refer to big tech firms and their leaders such as, you know, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, etc. Professor Perry mentioned Elon Musk, and so it's definitely an interesting situation.

But I think that rather than capturing the government, many of these tech firms have been consistently targeted by both Biden and Trump administrations over the past many years. And they've faced a lot of antitrust actions abroad.

But for now, I'll just focus on the charge that they're powerful monopolists, because I think this underlines the argument that big tech leaders comprise an oligarchy. So, I believe the argument is that they rely on their market power. They have significant monopoly power, and this is the basis of their economic power, which drives the political power.

So, to the first point about monopoly power — I just don't see that these firms are lethargic monopolists. They have many competitors, large and small, in their various markets, and they tend to increase competition in the markets they enter. The big tech firms compete vigorously with one another, most importantly. Amazon, for instance, competes with Google in specialized search. Google and Apple compete vigorously in smartphone and app markets. And Amazon, which has been called a monopolist in e-commerce — but most retail sales actually take place in brick-and-mortar establishments, and competitors like Walmart are catching up in online retail.

All these platforms compete with one another for consumers' attention, and I think rather than an oligarchy whereby you would see agreement among a small number of players to share large segments of important markets, these platforms are consistently at each other's throats in the marketplace. So, I don't think a technical oligarchy is going on.

And second, I would highlight that lobbying and other attempts to influence policy tends to emanate from the government's power to help or harm businesses. So, while these companies have been mostly focused on consumer experience, they get drawn into the political arena by power of the state. And so, this aspect really is the power of overreaching government that we should worry about.

As long as government isn't explicitly protecting large platforms or erecting unnecessary entry barriers to these industries, these firms will continue to face immense pressure. And I think that results in this claim that they have excess monopoly power to be overstated.

Professor Perry, America has been a society that has always had a capitalist model of economy and large corporations. And what you mentioned—the robber barons—have played a huge role in politics. Yet somehow, Elon Musk's intervention feels unprecedented. How’s that? What separates the new crop of tech oligarchs from the previous robber barons that we have seen in the Gilded Age, be that John Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan? What is the difference here?

I think one important difference is the fact that, of course, he bought Twitter, now known as X. And in that era, particularly starting in the early 1900s, you had someone like William Randolph Hearst, who would be considered a media mogul and had quite a bit of political influence and began what we call in history yellow journalism or sensationalist journalism.

And it relates, for example, to pushing America into the Spanish-American War under the William McKinley administration. Interestingly enough, William McKinley is a hero of Donald Trump, in part because William McKinley believed very strongly in imposed tariffs.

But I would say that combination of, again, the extreme wealth of Elon Musk, the amount of money that he contributed to the Trump campaign on this second—or rather third—run for the presidency, second successful run for the presidency, and the media influence that he can have and does have through the platform previously known as Twitter, now X, again makes a unique combination.

In addition to which, the slashing and burning and chainsawing of American government—that, if there are concerns among that group of businesspeople that government was too strong or it was preventing them from being as free as they would like in a capitalist system and a so-called free market—they can take pleasure, I think, from the extreme reduction of the number of people working in the government, the number of agencies in the government, and not in a way that actually addresses what they say they're addressing.

That is, Elon Musk and Trump say they're dealing with waste, fraud, and abuse in government. First of all, I would ask that people look at most human institutions—probably have some form of waste, fraud, and abuse. I'm willing to accept that that's probably the case in government. However, there's not been evidence of waste, fraud, and abuse that has been pointed to directly and with evidence.

And then a reduction in force, or even the elimination of an agency—which Al Gore did along with Bill Clinton in their reinventing government initiative back in the early to mid-1990s—in other words, they in a rational way went about reducing the size of government, the number of programs, and the number of agencies that they deemed to be ineffective.

So again, I think that’s a difference. And the other would be the people that you named, interestingly, became philanthropists. So, the Carnegie Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Mellon Art Institute in Washington, the Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh—there again, maybe at one point they were robber barons, or maybe they will always be considered that. But at least eventually, someone like Bill Gates—perhaps in response to the antitrust suits that were being brought against him and Microsoft by the government—he and his then-wife became philanthropic.

True. And I feel that spirit is somewhat missing today—the spirit of giving back to society. Mr. Giorgio, even if we disregard the monopoly part of the large, supposedly tech oligarchs that we are talking about and say that, oh, they do not have a monopoly in the market share—the fact is these tech tycoons among themselves can divide how we communicate with each other on social media, on our WhatsApp. And they're also the pioneers in emerging technologies such as AI, which is built on data sets that they derive from the platforms that we have been using for so long. And they have this unprecedented power to be able to have control over our lives through surveillance, through suppressing our speech, or putting us psychologically into conspiracy rabbit holes. Do you think that is sort of alarming—that the kind of technology that they are controlling or they are pioneering might set a trend for a future where we are under this constant surveillance of tech-enabled, government-supported systems?

Thanks for the question. It's a very interesting topic. I would just say that new technologies that increase the ability of firms to exploit economies of scale is nothing new. So, with the onset of new technologies, we would even expect some firms to continue to get larger through software algorithms. This causes firms to be able to exploit the economies of scale and to grow large. But also, with the increase of new technologies—now we have AI, not just software and algorithms but with increasing innovation—you have this dynamic where some firms take advantage of the economies of scale because they're in a position to do so, and they get large. But this also reduces entry barriers for new and smaller firms.

So this creates something that, in economics literature, is referred to as dynamic competition or innovation competition. This is when new startup firms or other large competitors will try to innovate, take advantage of new technologies to innovate, to leapfrog those who currently have a dominant position.

One example to make it concrete would be Google. So Google has what people call a dominant position in search, but they face serious disruptive pressure from AI that could make their traditional search business obsolete. So one thing that these tech companies have tried to do is invest heavily in these new technologies so that they can, in fact, disrupt themselves and create new products that end up making their own traditional businesses obsolete.

And so the businesses that will continue to succeed into the future are going to be the ones that are able to do this successfully. It's not about sitting on your laurels and being able to take advantage of your position. As long as government, again, is not erecting barriers to entry, these companies are going to face significant pressures. And they're not going to be able to just sit on their laurels. To be successful, they have to continue disrupting their own markets. And if they don't do so, new technologies like AI are going to make them obsolete.

So I think that we can be optimistic that these markets will continue to be competitive in the future.

Professor Perry, I want to give an answer from a historical point of view. We see that Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg have fallen in line with some of Donald Trump's policy. Meta has done away with DEI measures and fact-checking on their platforms, and Zuckerberg has also called for a more masculine workplace—whatever that means. What is this interrelationship between populism, capitalism, and masculinity—whether toxic or not—that we are seeing now, and how do they sort of feed into each other?

Yeah, as you can imagine, as a woman, I'm really interested in this. I don't know what to call it—a rebirth of references to masculinity. A concept that I'm reading about and very interested in, and I'm glad that you brought it up. I suppose the concept of DEI, for example—diversity, equity, and inclusion—results, I think, from the initial concept of affirmative action.

That was a concept that goes back to the mid-1960s, in particular when Lyndon Johnson, President of the United States after President Kennedy, had passed through Congress the 1964 Civil Rights Act. President Johnson gave a commencement address to Howard University, a traditionally Black university in Washington, D.C., and he said at the time that it doesn't help to offer equal opportunity to a group of people who, first of all, were enslaved in this country, and then secondly, kept down in society by the so-called Jim Crow system of the South—of prejudice and biases against them around the country.

He said it would be like taking an athlete who had been shackled—literally—and then bringing them up to the starting line of a foot race with an athlete, let's say, an Olympic-trained athlete, who had had all the opportunities of diet and expert training and was really ready to go—a top athlete—and firing off the starting gun, and expecting that the person who had been shackled and not had the other training opportunities could compete against the person who had all the training and benefits.

From that developed this notion—going back to 1978 in the Supreme Court and the Bakke case—saying in a very narrow majority that Justice Powell argued that Harvard could take, in theory, an entire entering freshman class of white prep school boys from the Northeast who had perfect test scores and 4.0 averages. But if they had all of these students, and then they had others—someone like me, who was a first-generation university student wanting to get into Harvard from Kentucky, and being a female—and I did have, by the way, a 4.0 average coming out of high school—so he said if they wanted to diversify their entering class, they could do so.

That led to the controversy—which I well understand as a constitutional scholar as well as a presidency scholar—that the 14th Amendment would seem to ban any other consideration other than merit from these kinds of decisions, whether they be in employment or in higher education.

So, I think that this notion of decreased masculinity, as diversity became the watchword among liberals and among the Democratic Party, has led to this concept that liberalism has led to a lack of masculinity. I also think the trans issue—the transsexual issue—has entered into that in the popular consciousness, which again, I well understand because it seems an oddity to many Americans. I think even left-leaning Americans don't necessarily comprehend the entire thought about transsexuality.

So, I think that brings us to where we are in this combination of populism, which is anti-elitism, anti-expertise, anti-university, and anti-scientific knowledge—anti-vaccine. It has led to a demasculinity of the American populace, and talk about moving people back from elite white-collar, ultra-educated jobs to manual labor.

I'll just throw this out—not because I necessarily believe in it—but I'm reading and hearing more that people on the left and liberals are saying, "Oh my goodness, this is like the Maoist Revolution—the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s under Mao in Communist China." So people can have that as food for thought.

Mr. Giorgio, even if we say that, you know, they don't have a market share as huge, the creative cycle won't be disrupted. But can we agree that some of President Trump's policies, or the way they have been implemented, have been polarizing for the people of the USA? Also, now the global order, with his tariff measures—now to my mind, wouldn't it make sense for capitalists and industrialists to have a more stable, liberal society, allowing for innovation and growth instead of a society that is polarized and always on the boil, and then sort of accepting these measures, these ideologies of President Trump—calling for a more masculine workplace, dismantling DEI measures—have they not given in to this populist kind of politics?

I find the topic very interesting, although it's outside of my area of expertise. I do believe that, as you mentioned, I believe personally that the focus on innovation should be and economic growth. So innovation and economic growth should be more of a concern in government economic policy. I do think that the tariffs can have negative effects, but I take the position that my colleagues at ITIF who are working on this issue, and I would point you to their new work on a report which they call Globalization 2.0, which is a better strategy focused on economic growth and innovation for the U.S., in which we are aligned more with our allies. So we're reducing trade barriers with our allies but focusing more on working with our allies and strategic competition with China to counter the sort of trade practices or harmful trade practices and state-backed economic policies that are going on there.

So I do agree with you that we do need to focus more on innovation and how we do that in economic policy concerning large tech firms is to focus on this innovation competition that comes from continued technological innovation, which promotes creative destruction. Creative destruction is a term that was coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter in the early 20th century, and that refers to the essential nature of capitalism, which is new technological development continually destroying current methods of doing business or of reaching consumers, and basically capitalism continuing to reinvent itself in this way.

Schumpeter's main focus was how this, in the long run, drives increasing economic growth and welfare for people. So I think one thing is to not arbitrarily target specific firms because it can decrease their incentives to continue innovating, and to take a light-touch policy with regard to regulation with new innovation, with new technologies such as AI, that have the potential to keep this creative destruction going—give us new types of services, new ways of doing business that we can't even potentially think about yet, but that are going to make these current methods of business that we can't picture living without—in the long run, will make them obsolete and will make society wealthier.

So I absolutely agree that that should be a focus, and I do take that position.

So I think to sum up the two sides, I would say Professor Perry is more cautious about what is happening and has some doubts about whether this would be good for American society or not. Right?

Yes. And I would just use the last three—almost three—months now of experience, and not only that, but where the stock market is, particularly because of this tariff regime. But also it does concern me to see the government hacked almost to death in terms of what is called, somewhat disparagingly, the administrative state. But you know, I would point out that even starting with Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, when 25% of Americans were out of work and losing their homes and farms, and businesses were shuttering, and farms were going by the wayside, and there was a terrible climate crisis in the Midwest—that nothing private, nothing charitable, nothing local or state could handle that. Not only a deep depression in this country, but a worldwide depression. And so that's when we've called upon the government, and it indeed expanded the powers of the president—expanded. And so we in political science need to keep an eye on that. But it disturbs me to see not only the world situation, with the United States at the leadership of the free world, as we call it, diminish because of economic policies and an anti-government position of this current administration.

But I think Mr. Giorgio would argue that, though this is a major disruption, this is nothing that we have not seen before. There are opportunities for creative disruption and for some new economic forces to emerge, and this is not a case where monopolies or a few industrialists are running the world and the American economy.

Yes, thanks, Heena. I think that's right. I would definitely say that. I would also say, in the specific case of Elon Musk—well, I don't know, of course, what's going on in his head. I'm not Elon Musk. But a lot of the activity that he's engaged in doesn't seem to be guided solely by business considerations.

One thing you would expect to see when industry figures are capturing government is that, at least in the economics literature, one thing you would want to look out for is a direction of new entry barriers or these industry leaders using government as an easier way to collude with one another.

As I mentioned previously, I think they're competing with one another rather than colluding. In the case of Musk, in the previous months, while many auto brands saw a surge in purchases because of the tariffs—many consumers got out to get their new car to get ahead of new tariffs—Tesla revenue and sales have taken a big hit globally.

I think if Elon Musk were doing what he's currently doing only to solidify economic power, if consumers don't want what you're selling, it doesn't matter how much monopoly power you have over a given product. Getting involved in politics is not necessarily, in the way that he has done it, a good thing for his business. He has many competitors to deal with in Tesla and Twitter, etc.

Many companies try to avoid any speech that would be construed as political or taking political positions because this can turn off consumers. Ultimately, in the market society in which we live, which thankfully is not ruled by monopolies, consumers have lots of places to turn. When these industry leaders engage in politics, it often turns off consumers, and they're able to switch away from those products.

Furthermore, I would say that, in a sense, there's nothing new here. A few years back, we had Sam Bankman-Fried, who was backing somebody running for a congressional seat in Oregon. He spent, I think, over $11 million—that was unsuccessful. Ross Perot in the '90s ran and largely financed his own presidential campaigns. We see businessmen and women getting involved in politics all the time. Some of this involves campaign finance and things that we won't go into here.

But Musk is an interesting case because he's so close to a particular president. I think that, in one sense, there's nothing new here as well.

I want to end on an optimistic note. From whatever side we may see, the scene is a little chaotic, but what growth opportunities do you see for society as a whole and for the world of technology in particular, Professor Perry?

Well, I agree with my expert colleague about the excitement around technology. Just think about how even a few years ago we wouldn't be meeting this way. And so, those of us in the academic world who use this for our research purposes and getting our scholarship out before a larger public audience is very exciting. I particularly work on presidential oral histories at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia. We are a nonpartisan organization that has done oral histories of every presidential administration starting with Gerald Ford. We are finishing up on the Obama project and we are starting into the first term of the Trump administration. We are using AI now to be able to harvest the information that we have gathered over 50 years since we were founded.

And so that is my optimistic note about technology. As a political scientist, I'm less optimistic about where our government is heading and where our constitutional structure is heading. But I am a very pro-American, patriotic person—the first in my neighborhood to put out my flags of the United States on federal holidays. So I will always be optimistic about the United States. But I'm a little bit concerned now both about the economy and about our constitutional structure.

Yeah, I see in the economy, I think, a lot of reason to feel optimism about AI. I'll talk about AI as well—it's on everybody's minds, and also mine. I think it has the potential to be very transformative. Of course, we need to realize that there can be risks, and we need to think hard about how to deal with those in a way that doesn't overly restrict what people can do to innovate and start new businesses with AI.

But I'll just use one anecdote from my personal life. So at my university, I often help with tutoring young students in the athletics department who need help with their classes—young athletes who need help with things like calculus or economics. I have used this to prepare. I've used AI tools—various ones—to help prepare and help these students.

I think that the technologies are getting so good now that they can largely— I can foresee that you could just have students using their own AI and an LLM or something like this, and using it to great effect to help them out with their own classes. In one sense, you might think it could replace tutors, but I actually think there's a lot of opportunity to have tutors who are trained to prompt-engineer for tutoring with AI. So, humans working with these machines and these tools in order to enhance their capability to help students on certain subjects.

I actually think that there's just one small area where AI could really increase productivity and help people. But I think there are probably many other examples that we haven't thought of yet, and I'm very optimistic that that's going to be the case.

Thank you so much, Professor Perry and Mr. Giorgio, for joining me on this panel discussion.